18.12.19 – The CHEOPS satellite was put into orbit on Wednesday, a day later than planned, from the European spaceport in Kourou, French Guiana. The telescope, which will hunt for new exoplanets, is the result of six years of collaboration between the University of Bern and the University of Geneva, with the assistance of EPFL’s Space Center.

Mission accomplished! The CHEOPS satellite, named for “CHaracterizing ExOPlanet Satellite,” successfully blasted off into space on Wednesday after a technical fault with the carrier rocket pushed the launch back by 24 hours. The satellite, which will search for planets orbiting around distant stars, is now flying along its planned path, some 700 km above the Earth’s surface. CHEOPS is the culmination of six years of work, much of which was carried out at the University of Bern and University of Geneva, in collaboration with researchers from EPFL’s Space Center (eSpace) and with support from the European Space Agency (ESA). The launch comes seven days after two astrophysicists from the University of Geneva – Michel Mayor and Didier Queloz – received the Nobel Prize in Physics in Stockholm for their 1995 discovery of the first exoplanet.

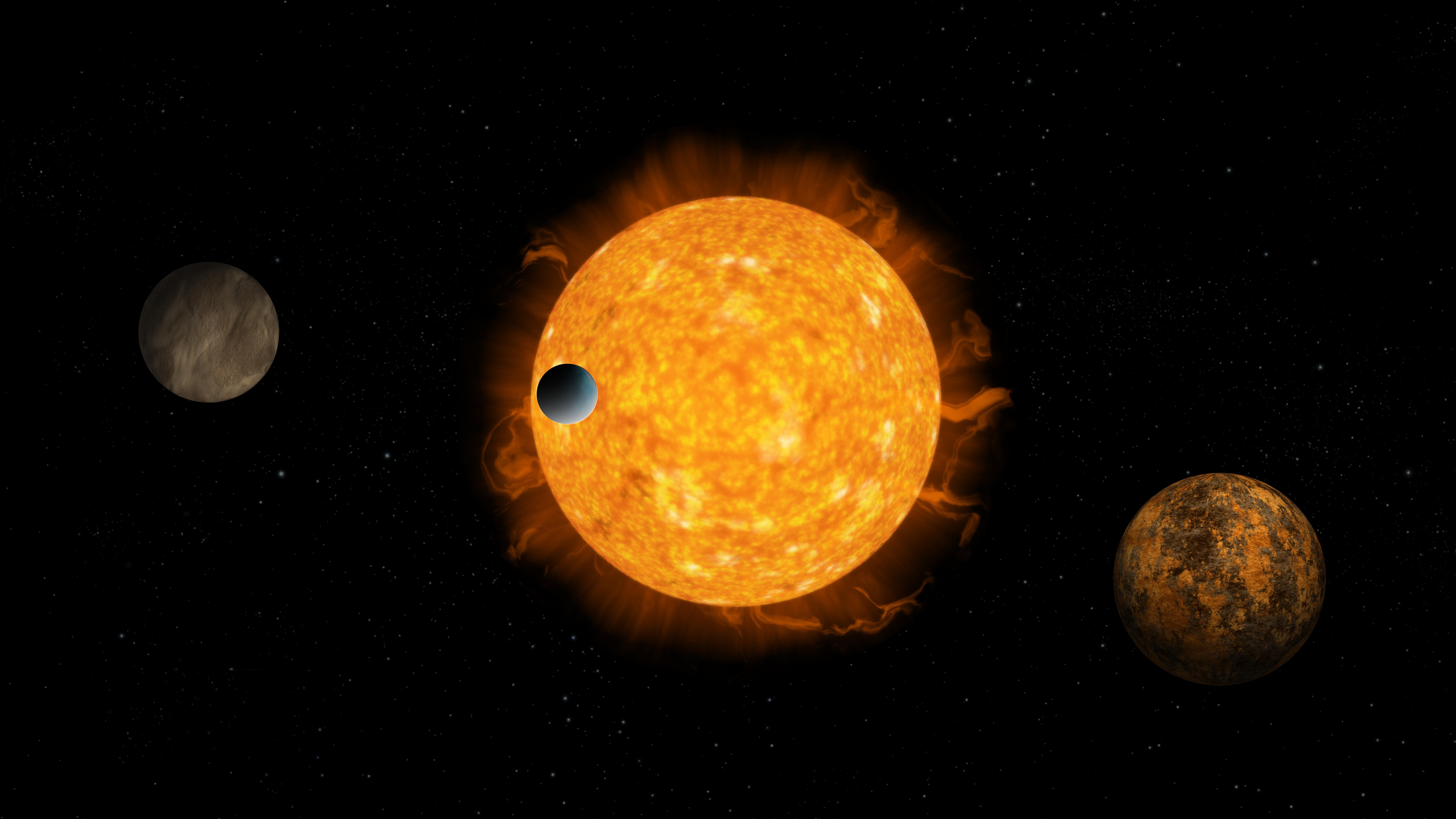

The satellite, which is equipped with a high-precision telescope, will seek out new exoplanets by looking for tiny variations in a star’s brightness as a planet passes between it and Earth – a method known as transit photometry. CHEOPS will also gather more information about known exoplanets, including their size, orbital elements, atmosphere and evolution, as well as their composition and nature: telluric, gas, ice giant, surface water and other features.

The satellite, which is equipped with a high-precision telescope, will seek out new exoplanets by looking for tiny variations in a star’s brightness as a planet passes between it and Earth – a method known as transit photometry. CHEOPS will also gather more information about known exoplanets, including their size, orbital elements, atmosphere and evolution, as well as their composition and nature: telluric, gas, ice giant, surface water and other features.

EPFL involved from the outset

The project was a collaborative effort between three Swiss institutions: EPFL, the University of Geneva and the University of Bern. Engineers at eSpace were involved in the early phases of the mission, and worked on the satellite’s initial design. In 2012 the ESA selected CHEOPS, based on that initial design, as its first small-class (or S-class) mission, a type of smaller-scale program intended to promote innovation and education. From that point on, EPFL’s involvement largely revolved around designing the software that would be used to analyze the raw data sent back by the satellite.

Since the first exoplanet was discovered in 1995, over 4,000 more have been added to the list – orbiting around some 3,000 stars, and all within 400 light years of the Sun. Thousands of other candidates have been detected, mainly by ground-based telescopes, but are pending confirmation. Extrapolating these numbers suggests that there could be at least 100 billion exoplanets in our galaxy alone.

CHEOPS separated from its carrier rocket around 2 hours and 30 minutes after launch and is expected to begin sending back data in early 2020.

Picture: (c)ESA